Why Pluriversal Practice Can Strengthen Our Movements for Justice and Liberation

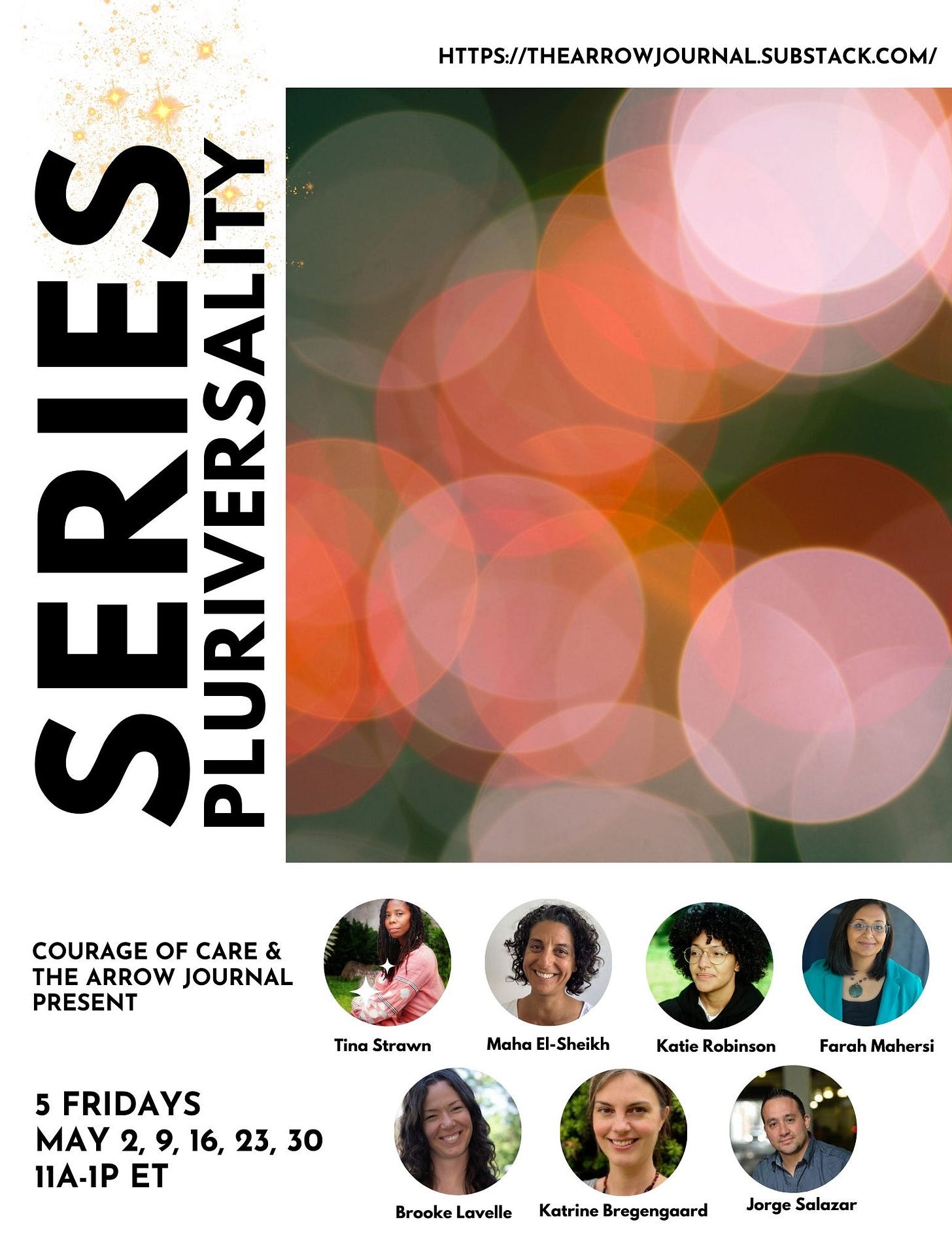

A roundtable with Tina Strawn, Farah Mahesri, katie robinson, Maha El-Sheikh, and Brooke D. Lavelle

“Many words are walked in the world. Many worlds are made. Many worlds make us. There are words and worlds that are lies and injustices. There are words and worlds that are truthful and true. In the world of the powerful there is room only for the big and their helpers. In the world we want, everybody fits. The world we want is a world in which many worlds fit.”

Zapatistas: Fourth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle

The following roundtable essay from our recent issue of The Arrow Journal is a discussion between five friends and facilitators from Courage of Care—a non-profit focused on building liberatory cultures of practice and new home to The Arrow Journal—who gathered to create a new course, Sensing Alternatives, in the summer of 2024. The course was a response to challenges, blocks, and variations of “stuckness” many of us had been feeling in our communities, organizations, movements, and cultural worlds. We each sensed, in our own ways, the growing fracturing and fragility of so-called progressive movements and spaces, as well as an inability for folks to meet each other in their fullness and complexity. These fractures and reductive ways of relating to one another were undermining the relational fabric of our groups, and also wearing away at the foundation of our movements.

Together, we aimed through our course to help folks catch on to these limiting habits of “one-world-worlding”, by which we refer to hegemonic tendencies of our so-called progressive spaces to suggest that there is “one right way” to think, organize, and act. As we learned to catch onto these limiting patterns, we began to explore practices and strategies for countering them through embodied practice. We share some of these practices below and also discuss them in further detail in another essay in this issue. The conversation that follows here, edited from the original for readability, attempts to provide more context for why pluriversal practice matters and how it can strengthen—and not divide—our movements for healing, justice, and liberation.

Read the discussion below. You may also download and share the essay, linked below as a .pdf.

Please also consider joining our upcoming workshop on March 28th and our five-week series in May on pluriversal practice.

Brooke: Welcome, Farah, katie, Maha, and Tina. It is good to be together again. Our time together in planning meetings and live course sessions as well as the voice notes we exchange always feels so deep, easy, and emergent, and I’m looking forward to talking with you all today about pluriversal practice. What is the pluriverse? Why does this conversation matter for folks working towards healing, justice, and/or liberation?

Farah: The pluriverse, for me, is the answer to the question, “what are we building for?” The opposite of that question, “what are we against?,” is often easier to answer, particularly, I think, for those of us who embody intersectional identities and feel the magnitude of oppression. We can see and feel it in our bodies and thus it is often both easier and more urgent to be able to name that which we are against. That is the sense of justice in us—the part that can sense the wrong around us, that knows we stand against injustice. The liberation in us—that’s what requires us to dream.

And I think that’s also by design. I think that the “one world way” of being has been ground into almost every part of our being and every part of the fabric of our society. But at the end of the day, building for liberation is building towards something, and the pluriverse is that answer. It is the answer, and it's also the invitation for us to all kind of pull out of everything that we are surrounded by and to dream and to explore this possibility to lean into this idea that these colonial constructs—these one world constructs—these white supremacy constructs, they aren't the only way of being. In fact, that was the project: the colonial project, the white supremacist project, the patriarchal project, the one-world project was forced upon us. So for me the pluriverse is that invitation into liberation. Partly, it is the space to breathe and to be and to imagine and to think and to dare and to be safe and to be all of these things all at once. I think this expansiveness is partly why it's hard to put our hands around it.

Maha: I’m struck, Farah, by what you just said about the pluriverse as the invitation to also dream (that there’s another way of being), and I’m just reflecting on how my body just soaks that up and gets so excited when it hears and feels that.

I’m remembering, too, that my body forgets that possibility when I'm really stuck in that “one-world world,” especially when doing movement work that is really focused on fighting the system, tearing down the system, fighting oppression—which of course needs to be happening. But I'm also realizing how narrow that can feel sometimes. And I’m appreciating taking the opportunity to pause and remember that there isn’t just one solution, right? There are many solutions, many strategies, and when we remember that we avoid the siloing that can happen in our movements—yes, even the “one right way” in our movements for justice—and remember there are many possibilities. That reflection brought some spaciousness to me right now that I was lacking.

katie: I can pick up from this sense of other possibilities. In Pluriversal Politics, Arturo Escobar wrote “another world is possible because other reals are possible and other possibles are possible.” The bottom line for me is that multiple worlds literally means different things are real to different people.

For some people, you know, the brain is this hunk of meat and there's nothing else and we're just very biological, very mechanical; that's one way of seeing the world and what we are. For other people, we are being animated by generations of ancestors and predecessors; time doesn’t work the same way; everything around us has consciousness; the wind remembers things, and drums can say things. In a very literal sense, different things are real to different people, which means that different things are possible.

In terms of the pluriverse, then, there isn’t just one real. The one-world-world would have you think that science says X; we know things because we can prove and repeat them. Other worlds or frames might respond: well actually, the things that are unique are more real than the things that are repeatable.

There are all of these constructs that we take for granted in our being, and therefore we take them for granted in our movement work, which, in turn, limits our movement work.

Tina: The pluriverse as an answer to a lot of the questions that I and other movement leaders are hearing from people. A lot of us are being asked things like, “Well for you folks who want a revolution and freedom from or an end to colonial, empirical projects, tell us what to do! What’s the plan?”

The answer is to embody the pluriverse. I can’t tell you what it looks like. I can’t give you a single answer. It’s not one thing. It’s what you want it to be.

I’ll use the example of something I said before which is that the United States of America is the white man’s wet dream. This colonial project was dreamed up by a small group of people, largely white and male, to benefit another small group of people, also largely white and male. We happen to find ourselves living in an oppressive society inside their dream. So the pluriverse is the dreamscape, the dreamworld. We didn't consent to participate in colonial, empirical projects, but we can choose to be in the creation of what we want.

We are positioned between our ancestors and our descendants, between what came before us and what will be. Thepluriverse is building what will be, and not building it as though it is far off and removed, but building it in such a way that we are living into it right now. The answer to your question—What is the pluriverse?—is that it is whatever we choose, desire, and come together and create.

Brooke: When we say things like multiple realities and multiple truths exist, and that the pluriverse is whatever we want it to be, are we talking about moral relativism? Does anything and everything go in the pluriverse?

Tina: I come back to people wanting us so badly to have the answer and to tell them the answer. That is such a binary, colonial way of thinking. The implication that the pluriverse is moral relativism is based on the idea that the only alternative to this world or the one world is anarchy. Now,I'm not opposed to anarchy, but there’s also so much more to this. Even the suggestion that the pluriverse means that “anything goes” feels like it's coming from this desire for control. Empire operates on that control; it wants us to conform and presents the alternative to that conformity as being wild and savage and structureless and order-less.

But we don’t even have to use that type of reasoning or these limited ways of thinking and being. I’m pushing back on the idea that the pluriverse means anything goes…or what? Nothing goes? Whatever. Start somewhere. Seek what you want. Dream. Create.

katie: I agree that thinking about pluriversal practice as a moral relativism is a one world way of approaching this question. In a one-world reality, there is only one world, which means that we're all in the same version of reality in which only one set of morals can exist. This puts us on the spectrum of moral relativism. If you understand this conversation pluriversally, you will understand that if you live in different realities, there are multiple moralities, or multiple spectrums, based within the constructs of those different realities. Or, in other words, what is moral in one world may not be in another world because those worlds are different. They are incomparable, or incommensurable.

So, when you get into these conversations about pluriversal practice and morality, unless you can understand the concept of multiple realities, things start to break down quickly. You can tell easily in conversation with someone when you’re in a one-world-world reality versus a multiple-worlds reality. The sense of possibility is vastly different.

Let me give a concrete example from the abolitionist movement. Something that Mariame Kaba says is that there is not just one alternative to prisons. It's not just that when we imagine the end of prisons there is one vision or model for how the process will unfold. How we get there—whether it’s through restorative justice, community protection models, defunding the police, etc.—depends on the reality and conditions of your community. If I'm over here in Minneapolis, the “alternative” to prison is going to look vastly different than if I'm on the other side of the world because we're in different contexts, different realities. If for example, you're in South Africa and the idea of ubuntu is part of your reality, then your idea of justice is going to look different than if those ideas of relationality have been generationally robbed from you, if you're in the United States, for example. That is just one example, but you can tell when something is in the pluriversal space and when it is not.

Farah: I just want to add that the pluriverse is the space and the dreamscape, and there is still work to be done. The project of Liberation is an active project. The pluriverse is not an end or an ultimate answer. In the pluriverse, we will still have to be relational, we will still have to show up with care, we will still have to think deep thoughts, and we will still have to show up and be active.

I think it’s a mistake to equate the pluriverse with some utopia in which we will just become these passive bots that just float through life. I really want us to root in the fact that there will always be work on the path to liberation. There will always be engagement. I am naming this explicitly because I don’t want it to come across as really easy. These questions we’ve been wrestling with—is it moral relativism? Is it anarchy? What is the pluriverse? How does it help us in movement space?—are the questions we will continue to have,process,work through, and interrogate along the way.

Pluriversal practice is the practice; it’s a way of also showing up day to day; it isn't a panacea. It isn't the golden answer that’s arrived. This is important for me to name because sometimes I sense that we are in movement groups and spaces in which people are so tired. We are exhausted. Our souls ache. So we grasp at this idea that we will arrive at a place and then there will be no more work, that we will then get to rest. And this vision is so tempting. It's like it if we do enough, rest will be our reward. And that, by the way, is why embodied practices and building rest along the way are so critical. Because, the work is liberation. And because the work is liberation, it is never-ending. The work for liberation is never-ending. The love for liberation is never-ending. And so the pluriverse again is our way to liberation. It is our way to exist in liberation. But, if we do the work while embracing the pluriverse, the work won’t feel like such a grind.. It can become something different; something beyond “fighting injustice.”

Brooke: I want to ask a question about models of liberation in relation to pluriversal practice. In short: what do we mean when we say liberation?

I’m aware that diverse spiritual and religious traditions embrace different models of liberation. Some, for example, say liberation is found elsewhere, as in heaven or in freedom from the samsara or the cycle of suffering. Others may say that liberation is not only possible but is to be found right here: that heaven and hell or samsara and nirvana are not ultimately separate. Still, some models privilege individual paths whereas others hold that individual liberation is only possible via collective liberation. I’m simplifying vast and complex schools of thought here, but am raising this general question because I think it is relevant to our healing, justice and movement spaces.

I think we not only have different understandings of what terms like justice and freedom and liberation mean, but also where they lead. I certainly sense that different working models of liberation pervade our movements. In my view, these models of liberation shape what we sense is possible, how we practice, and how we organize.

At the same time, I think it matters, especially in terms of pluriversal practice, that we are able to entertain and embrace multiple models of healing, justice, and liberation because I think readying for multiple futures and possibilities makes us stronger. I make this connection often with the climate crisis: whether we believe the world is ending and we are headed for mass extinction, or whether we believe everything will be fine with or without significant organization and intervention will impact what we think is possible, how we strategize, how we show up, and whether and where we allocate resources.

So, back to my question: what do you think? Where are our movements in terms of embracing multiple models of reality? Multiple truths? What are the models of liberation that dominate or pervade our spaces? Can our movements hold multiple models of liberation? What are we ready for?

katie: I love this question. Things are popping off in my brain, but first and foremost for me, based on my personal experience and my own healing journey, I agree that what we believe dictates what we think is possible. And, as we practice, we change or influence or reinstate that model. So for me, learning about ontology, learning about multiple realities and multiple universes and so forth felt like a cheat code, because it showed me that, “oh, I can choose what to believe in and therefore I can choose my reality.”

Now, obviously, it's not that simple. We don't want to collapse into these simplistic ideas of just thinking yourself free; I’m not trying to do that. But what is super important—and this is where I think the Abolitionist Movement and movement in general is ready for—what we believe we are doing when we are doing it matters. What we believe when we are at a protest, when we are at the coalition meeting, when we are standing up at the DNC trying to disrupt and talk about the genocide, matters. It matters if you believe you are acting alone. It matters if you believe you are a part of the earth reaching up to do what the earth needs you to do. It matters if you feel like it's you against the world. It matters if you feel like you're literally surrounded by ancestors. Your frame will change what ends up happening from your action.

So, I think before we talk about readiness for embracing multiple realities there's a quote from the book, End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, that talks about the need to reinterpret the world before trying to change it. I think that we've been trying to change the world before trying to reinterpret it and I think we need to do some reinterpretation before we venture to try to change it. If we don’t, we're just going to do colonialism all over again.

Farah: Yes. Everything katie just said. Our beliefs matter. The one addition I would add is that our intentions also matter.

I think we've also been pushed into this world where intentions don't matter— only actions matter—and because we don't live in a pluriverse, we collectively believe that only our actions matter. While our actions matter deeply because they impact other people, the intentions behind those actions also matter. The way we conceptualize the world matter, and the intention we set when we show up to a space also matters.

This is the fun part to me: as someone who is both spiritual and religious, it is the moments when I can sit in a space, stand at a protest, be in a room, and be actively understanding the conversation through my particular moral, religious viewpoint. And—at the same time—I can be in full community with the person standing next to me who is interpreting and understanding what is happening through a different frame, with different intentions or beliefs, including often people who hold the exact opposite opinions about religion that I do. And I can still be in community and be relational with someone who is in the space with me but is looking through a slightly different lens, or operating from a different world. I think that's the part that freaks us all out!

Fear leads us to ask questions like, “How can you have different intentions and different beliefs and be in community with me? Are you an infiltrator?!”

Again, my response to these kinds of questions is to remind us all that this sort of immediate suspicious response is a conditioning of colonialism and white supremacy, which have literally ground us into a pulp. And while that response is natural and even understandable in response to the conditions in which we exist, our pluriversal practice is to set fear aside and to heal, move, and practice alongside one another with love and kindness.

I think movements are grappling with this deeply as well. I think we've extracted all the vocabulary and frameworks for talking about beliefs and intentions from our movement spaces. I think that we also struggle with goals, objectives, and frameworks, and we often conflate the tactic of the thing, like going to a protest,with the philosophy of liberation. Often I feel that we are talking at such different levels of analysis.

Our ability to step into pluriversal practice and be willing and able to stand next to each other and engage in the exact same tactic for reasons motivated by different intentions, beliefs, and frameworks is essential. I think a pluriversal stance is the essence of being human and of being free and liberated!

And it’s so hard because we are spending so much of our time trying to do this magical thing that we call “aligning.” Because while we use this seemingly innocuous word, the undercurrent of this is us implying that unless we 100% align on every single tactic that we use, we default to believing that we are NOT in community. And that means we are NOT in solidarity. And then, well, if we’re not in solidarity, who are we? And what are we doing together in this space?

And then we can start to believe things like my movement is more important than your movement, or my analysis is the analysis. I think that is where we are. And so I’m not sure if it’s just a question of the binaries as in ready or not, but maybe readiness is is tied to whether you have found your people around whom you feel safe enough and cared for enough to be able to step off that ledge and engage this broader idea of pluriversal practice and of liberation.

I've seen that in a number of places and movement spaces right where people— because we don't sit around and we don't talk about philosophy and deep belief systems and things like that—are kind of like, “oh someone else doesn't see the world in exactly the same way that I do and now I don't know what to do with them.” Right? And then that's where the pluriversal stance is something like, “You let them be them; you figure out how to be with them.” Or worse, we try to “one-world” them and their ideas into “alignment.”

Brooke: I think what you're getting at here is some of the one-world-worlding in our movements. And maybe it stems from fear of needing to belong in order to feel like we're on solid ground together, or needing to feel that we're the same so we know we’ll have each others’ backs when it goes down. Could you share a little bit more about where you are seeing or experiencing that one-worlding in our movements? And what would it take, in terms of practices, scaffolding, and/or frameshifting, to help our people and movements shift toward pluriversal practice?

katie: "One antidote I've experienced to "one-world-worlding" comes from our own relational facilitators and pluriverse series. In these somatic workshops, the specific exercise we've done move individuals and the collective from constriction to expansion and from urgency, faced-paced doing to a more intentional and sustainable pace. We also explore “worlding” somatically—by asking, for example, what is possible when you inhabit this or that “world” or “shape” or framework versus what is possible when you're in a different shape or frame. By shape or world, in this context, we mean the full set of embodied thoughts, feelings, perceptions, behaviors, and so forth that shape how we perceive and relate to our world. To me, these practices really ground this idea that there isn't just one set of possible. My experience can look and feel very different depending on the shape in which I am in.

For me, even though I've been wrestling with these concepts intellectually, exercises like that have been a major doorway into grounded pluriversal practice. In my experience, when you're in a justice-oriented space, everybody's in a shape or world, a kind of energetic habit or way of knowing, perceiving, and being. And everyone else’s shape or world can feel pretty contagious.

Here's one way to explain the one-worlding of shape. Have you ever heard someone in a community or movement say, “We are like this?” That’s the shape. That’s the forming and norming. That’s the one-worlding. And so the practice of simply slowing down and opening up a breath and asking, what is actually inside of you— and opening to the idea that different things might be possible if I come to this work in a different shape or world, or in or with the multiple shapes and worlds that I, and others, contain is key. It requires a kind of safety to release the idea or compulsion for everything to be neat or the same or singular. Or that we need to have the answer. Different thoughts, frames, ideas, and possibilities can enter, be witnessed, and be expressed by me when I'm not caught in shape or a singular frame, and that process itself might change what I bring to this space. And what I, and we, are able to contribute to our movements. Think about the power of that. The power to draw upon all of our gifts.

I think exercises that also invite us to deepen our ability to be changed are critical. I think we have to be available to be changed, and I don't think that we are necessarily always available to being changed.

Tina: katie, I agree with what you said, especially in relation to embodiment work.

I think understanding and exploring the shapes that we take in movement spaces is really important.

And I’ll be honest: I’ve tried as a movement leader to get everyone to take on fight shape! And that has served its purpose at times, but I also have realized it's actually misguided to get everyone into the same shape because that is a replication of colonialism. Liberation is not conformity or uniformity. Liberation is freeing ourselves from constraints and choosing to be in relationship with ourselves and with others in ways where everyone’s humanity is acknowledged, respected, and valued.

All of the shapes have lessons to teach us. As we heal, we begin to understand the ways in which “fight” for example has shown up in response to trauma. So trying on a different shape, like water, space, earth, or air, can illuminate a new way to show up in response to our capacity for joy, and that’s an entirely different framing.

Even the language that we use around “fight,” as in fighting the system, and even “work” situates us in relation to the current structures and systems of oppression. But if we relate to the “work” as where we sit in relation to the universe, then play becomes possible. And pluriversal. There are many kinds of “work” and many ways to do “the work.” Even just saying “play” to adults kind of explodes our brains a bit.

Farah, I feel like you speak to this really beautifully, about how it is a shock to our system to go back and forth between the “system” or the one-world and the alternative, more liberatory spaces some of us exist in and co-create. We spend so much time in the work and in the fight and then we have to transition to this other side or alternate reality. When we get to play and see what’s in our bodies and what’s arising, we’re giving ourselves an opportunity already to begin to dance in pluriversal practice. But play, creativity, imagination, and dreaming are not things that have value in “the work” as it stands in dominant, one-world culture.

Maha: I’m resonating with this so much. And I’m thinking about the necessity, at times, of rallying that fight energy to resist and to block, and also that the process of rallying that energy is the process of worlding. Of taking on a shape. When we are in that shape of fight, I like to ask myself and folks that I work with, “What does the world look and feel like right now? What seems possible? What seems necessary?” And we often notice that while there is almost always some wisdom and truth in these shapes, if and when we get stuck in a single shape, we limit our possibilities for other ways of seeing, feeling, and responding. What becomes possible when we take on the shape of working with? Or letting be? Or sensing what else is here?

This is an important pivot for us in Courage and also for movement work in general. What does it look like to not only be against something, but to work for something? To work for other worlds, realities, and possibilities that not only could come into being if we collectively manifested them, and/but the worlds that also exist right alongside this one? How might that pluriversal sensibility help us harness even more creative power and flexibility?

It feels important to name that we are talking about embodied practices to some extent, but we are also talking about culture change and world building. These are critical skills for these times. We sometimes say that the social, ecological, and economic crises of our times are relational crises that pivot on the logic of separation and domination. That separation is what permits the habit of one-world-worlding,or cultural domination, to emerge and continue. There’s a lot at stake.

Farah: I would add one other piece to this discussion of shapes that can help us visualize some of the tensions we’re sitting with. The reality is that we’re all multiple shapes. In this way, we are embodying the pluriverse internally by being many shapes, sometimes at once. And all these shapes both serve us and can hurt us. It depends on our intentions, and it depends on how we embody these shapes. It means we have to learn to be at peace with all these shapes, and how and when to be with them or work with them, when they show up.

How do we do this? How do we learn to embrace this internal pluriverse? Learning to embrace the internal pluriverse will in turn help us embrace the external pluriverse. I'm an educator at heart, so for me it always starts with learning. Learning the theory, but also learning the practice.

In terms of practice, some of the learning is understanding my shapes within myself, and the shapes that show up in relationship and in community with others. How can I accept who I am and learn to show up in spaces in ways that are authentic to who I am? This is not to say that whatever harmful or hurtful shapes I can embody shouldn’t be tended or worked with. Rather, it’s a negotiation and practice of learning to discern when to be with and accept, and in a way resist norming and one-worlding, and when to work to transform. I can't be in right relationship with myself or in right community with others without this kind of practice.

tina: Another example was the discourse around this recent presidential election. I could preach a sermon about it but I won't, except to say that it was a clear demonstration of the dangers of one-worlding. There was not only no space nor room for imagining, or dreaming outside of the dominant political parties, there was also tremendous emphasis placed on rejecting and villainizing anything that was outside of the two party system. Just the mention and consideration of third parties were met with fierce vitriol, accusations of anti-Blackness, and attacking revolutionary movements that insisted on organizing outside of the current electoral system.

Fear will always stunt the imagination. Fear is the primary tactic of the colonial empire to discourage and defeat pluriversal and liberatory practice. Fear is what white supremacy relies on to deactivate and demobilize, and what we saw during the election was a multitude of activated trauma responses. Shifting towards pluriversal practice means noticing the fear and the shape we take when our systems are overwhelmed and inviting in the possibility of choosing another shape, another way of being, of existing. That’s where healing begins and how we begin to bridge the gap from one worlding to what we will choose to practice on the other side.

Brooke: I’m aware that the outcome and effects of the recent presidential election are still very alive for many folks, and that even discussing the election might have snapped some of us right out of our bodies! I’m inviting a pause here so we can try to take in the full complexity of what you are inviting us to consider, Tina. We’ve been talking so much about the body as a site of practice, as a doorway to multiple worlds.

I know quite a few folks who stopped speaking leading up to the election because of political differences, including those who were otherwise seemingly aligned on most every aspect of their justice work, at least on the surface. The fault lines are real, and relationships built on this one-world-worlding are fragile.

katie: Yes. This is such a clear example of the need for more embodied practice that supports our capacity for complexity and pluriversal practice.

It also feels right to me to name the importance of taking the time to identify as best we can who our people are. And not in a tribal “who is in” and “who is out” way, but, rather, “who or what supports me?” Asking seriously, like, forreal forreal: “who is there for me? Who have I done hard things with? How can I nourish those relationships and our relational practices in this very moment?” We are going to need to know who we can turn to when xyz happens?

And by xyz, I am including the possibility that those of us in the US might need to consider our exit plan. I know Tina can speak to this best.

Tina: I think any exit plan starts with making a conscious choice around the questions should I stay or should I go. Further how you truly feel about staying or leaving speaks more to why intentions and beliefs matter so much. The thing that preceded my personal decision to exit the United States was my intention to get free in a way that allowed me to feel free in my body, in THIS current state of my queer, Black, woman identified body. There was no place I looked and found other people who looked like me experiencing what felt or looked like freedom. The necessity to feel free enabled me to look beyond the American empire’s borders.

The Blaxit movement (the modern day resurgence of Black Americans moving out of the U.S. either primarily or partially due to systemic racism and anti-Black terror and violence) was what I discovered when I decided to act on my intention. My oldest daughter often says that I am the first person in our family to ex-patriate the U.S. That means that the only thing I had previously seen was the one world: we stay and make it work. But I wanted and needed so badly to know if there was another way that I set out to find that other way, even going so far as to make it up as I went. What I discovered was thousands of Black Americans sharing their stories of how they got out. And though I didn’t find anyone whose story looked just like mine, I was nonetheless encouraged to go out and write my own story because there were just as many ways to leave as there were people leaving. Storytelling is foundational in pluriverse building.

katie: Yes, and I’m thinking about how we will know. How we will know when to stay, when to go, when to resist, when to fight, and when, even, to strategically comply. There has already been immense, incalculable loss. My gut feeling is that more is coming,for our people, the lands we have known, and our rights of course. I would add, and this is straight from Bayo Akomolafe, that we need to learn how to grieve well. How do we learn to lose and grieve in a way that increases the potential for more life?

Brooke: Yes, there’s an expansiveness that can arise through the practice of letting go of what we love and long for, including our visions of how the world should be. I’m not talking about giving up, but rather loosening our habits of grasping.

Amidst the uncertainty, fear, chaos, and devastation that is unfolding—some of it intentionally designed to overwhelm, shock, and disorient us—how do we know when to slow down, speed up, pivot, or pause? How do we know when to act? When to listen? When to wait? When to try to sift through the noise and when to respond swiftly and urgently? In even seemingly mundane situations, how do we know when to leave a job? A relationship? When to change directions? Take a different route? How do we know when to say “no” or “yes” with our full being?

I’m reminded and comforted by words of wisdom that Maha often shares with me in response to some of these questions. “Your body will tell you.” To me, the ability to entertain these many paths, many possible futures, many selves, and all that you have been pointing toward in our conversation is so core to pluriversal practice. I’ve so appreciated your expansiveness and your grounding in the body as a site of practice.

Thank you for all you are teaching me and offering to our communities so many ways to practice for the pluriverse!

Tina Strawn (she/they) is a joy and liberation activist, racial and social justice advocate, and author of "Are We Free Yet? The Black, Queer Guide to Divorcing America." Tina is also the owner and host of the Speaking of Racism podcast and she is the co-founder of Here4TheKids, an abolitionist movement to ban guns and fossil fuels. The heart of Tina's work is founding and leading Legacy Trips, immersive, 3-day antiracism weekends where participants visit historic locations such as Montgomery and Selma, AL, and utilize spiritual practices and other mindfulness based resources as tools to affect personal and collective change. Tina has three adult children, an ex-husband, an ex-wife, and an ex-country. Tina has a TedX Talk entitled, " Blaxit: The New Underground Railroad" She has been a full-time minimalist nomad since February 2020 and currently lives in Costa Rica.

katie robinson (any pronouns) is a writer, scholar, and interdisciplinary artist devoted to the exploration of what is present and possible outside of the white supremacist colonial imagination. Their essay, “Here’s How I Let Them Come Close,” a meditation on encounters, extraterrestrials, and the creative process, was featured in A Darker Wilderness: Black Nature Writing from Soil to Stars from Milkweed in 2023. They are currently a PhD candidate at Pacifica Graduate Institute, where they are writing a dissertation at the intersections of depth psychology, decoloniality, and police and prison abolition.

Farah Mahesri (she/her) works as a strategy, organizational and leadership development thought-partner and collaborator for social justice, nonprofit and philanthropic organizations. She previously worked at Tides Advocacy, a 501c4 organization, and its sister organization Tides (a 501c3 entity) providing strategic, political and compliance support to multi-entity organizations working to build independent political power and work toward collective liberation. In this role, she helped to develop and launch several power building funds including for COVID response and to support climate justice and political organizing; and created a peer learning program to connect progressive executive directors together. She also provided strategic and political advice to organizations such as Dream Defenders, Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, California Environmental Justice Alliance Action, Detroit Action and others. Previously, as a Muslim-American coming of age during the post 9-11 era, Farah worked with international organizations working on the anti-war/peace agenda. Since 2022, she has been working as an independent consultant supporting organizations to align strategy to operations and navigate the new realities of how we work and interact at work. She sits on the board of multiple organizations, including LA Defensa and Creating the Future and hosts a podcast on applying liberatory principles to the future of work. She organizes with Alliance of South Asians Taking Action. Farah lives in Oakland, California.

Maha El-Sheikh (she/her) serves as Co-Director of Courage of Care, and has mentored numerous individuals in on their healing and facilitation journeys. Maha’s approach is warm, spacious, and devotional—as a lover of poetry, especially of mystical origins—she has a way of guiding people toward healing with gentle and direct insights. With 20 years working in the international humanitarian sector, Maha’s work currently focuses on the social injustices underlying our global crises. As a facilitator, she is inspired by 15 years living and working in Palestine and Lebanon, learning how connection to heart, beloved community, mutual aid, joy, and compassion can serve as antidotes to oppression, colonization, injustice and violence. She is eager to support those working in the aid sector to not only find sustainable ways of working in the face of ongoing violence and destruction, but also to find ways of seeking alignment—personally and professionally—with values of love and liberation.Maha is also the co-founder of the first non-profit, volunteer-run yoga center in Palestine, and brings her experience in studying and teaching trauma-informed yoga, somatics, and meditation to explore the interconnection of healing, social transformation, and justice.

Brooke Lavelle, Ph.D. (she/her) is the Co-Founder and Co-Director of Courage of Care. She has been a student of Tibetan Buddhism for over 25 years, and has been teaching relational contemplative practice for nearly as long. For many years she studied, taught, and researched the diversity of compassion practices and their related frameworks of liberation. She loves (re)introducing practitioners to relational compassion and devotional practices, and is keen on helping both new folks ignite their practice and seasoned practitioners work with transforming obstacles to love on the path. She has a background in contemplative theory and embodied cognition, and grounds her practice in the body and in context. She loves to work with individuals on shifting frameworks in order to open up possibilities for practice and new avenues for relating more authentically and lovingly. Brooke has worked in spiritual communities as well as organizations and movements working for healing and liberation. She now runs a community house and urban farm in Brooklyn, NY, and is keenly interested in the micro-relational work it takes to sustain a collective, especially one working to ground in values and practices that run counter to the status quo.